Pilot Peter Barratt deftly weaves his helicopter through the morning fog, high above the majestic cedars of the Great Bear Rainforest. From these heights, the winding river systems below look otherworldly. An aerial vantage gives us x-ray vision, allowing us to see every pebble, boulder and log strewn across the river bottom, as well as the prized salmon that we’re after. “I remember fishing that spot right there,” says Barratt, pointing to a shady bend in the river below. “It was dynamite years ago.” Barratt, an avid fisherman and co-owner of West Coast Helicopters, has been flying over these waters more than 50 years and fishing them even longer.

Back in 1983, Barratt teamed up with Craig Murray, founder of Nimmo Bay Resort, and the duo helped pioneer heli-fishing, a radical concept at the time. The ability to access 50,000 square miles of terrain, including over 50 isolated rivers and streams, some of which very few humans had ever fished, let alone seen, drew anglers from around the world to the remote lodge.

While heli-fishing was the original calling card of Nimmo Bay, and still one of its biggest draws, conservation has become an equally important part of the lodge’s ethos. Barratt’s experience on and above the rivers have made him one of the area’s top fishing guides, but almost more importantly, a wealth of knowledge when it comes to the health of the region’s river systems. “Logging, fish farming, overfishing, and climate change are all greatly affecting the fish and as a result these waters and the surrounding environment,” says Barratt.

Many people hear the word salmon and think of a delicious entrée on a restaurant menu. And while many coastal communities rely on salmon for protein, their importance extends beyond food value for humans. These fish are a keystone species and the biological foundation of river ecosystems. Without healthy stocks, there’d be a domino effect of consequences.

When a salmon completes its life cycle and dies after spawning, it washes ashore to be snacked on by a bald eagle then eaten by a grizzly bear.

– Jen Murphy

Salmon runs function as pumps that push large amounts of marine nutrients from the ocean to the headwaters of otherwise low productivity rivers. These nutrients are incorporated into food webs in rivers and surrounding landscapes. At least 137 different species depend on the nutrients that wild salmon deliver. When a salmon completes its life cycle and dies after spawning, it washes ashore to be snacked on by a bald eagle then eaten by a grizzly bear. The remains supply nutrients for the surrounding forests.

In some areas, spawning salmon contribute up to 25% of the nitrogen in the foliage of trees, resulting in tree growth rates nearly triple than in areas without salmon spawning. Trees shade and protect the stream banks from excessive erosion. Eventually, those trees fall into the streams and form log jams that provide shelter for juvenile salmon and protect the gravels that adults use for spawning.

Salmon are also crucial to the area’s tourism. In 2012, Craig’s son, Fraser, and his wife, Becky, took over operations at Nimmo Bay. In addition to updating the cabins and adding new wilderness and wellness activities, the couple made a commitment to run the lodge as sustainably as possible. Their end goal: to make sure anything they took for the lodge—energy, fuel, food—was offset in a way that kept nature in balance. Salmon, used for food and sport, were a big take. How could the lodge give back?

Genetic diversity is often key to enabling a species to adapt to changing environmental conditions. In salmon, for example, some individuals or populations might carry genes that make them less susceptible to new diseases or warming waters, enabling the species to survive the loss of other genetic strains. A genetic database is used in British Columbia to find out where ocean-caught salmon call home, but this database is almost nonexistent for the Broughton Archipelago and surrounding mainland.

Of the more than115 salmon runs in this region only 25 have any genetic samples collected and only 7 have enough information required by researchers and the federal government to truly capture the genetic diversity of a run. The lack of data meant that decisions around fisheries management were being made without information to back them up.

Researchers needed more samples, but collecting them required man power and access to hard-to-reach runs, two things Nimmo Bay could contribute. In a three-month fishing season, Nimmo Bay averages three helicopters and 15 fishermen per day, visiting some of the region’s most remote rivers. Since its inception, the lodge has been catch and release. In 2015, Nimmo Bay added a new step to its fishing practice, a clip.

Catch-Clip-Release is a citizen science-based initiative developed in partnership with Sea to Cedar, a foundation dedicated to community and conservation stewardship projects in the region, and the Salmon Coast Field Station. The goal of the program, says Sea to Cedar director Scott Rogers, is to build a long-term, community-driven salmon genetics baseline that will help researchers study and protect regional wild salmon populations.

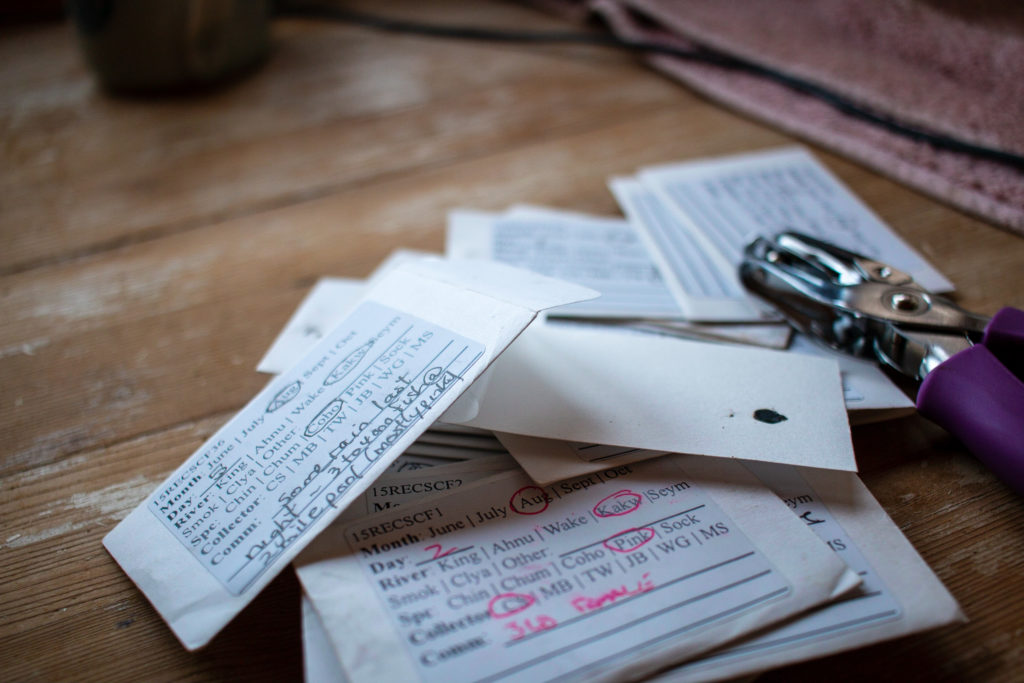

Nimmo Bay’s fishing guides received training on how to collect DNA and now fly with “clip kits.” After their clients catch a salmon, they take a small hand hole punch and clip a crescent of tissue from the adipose fin. This small fin between the dorsal fin and tail isn’t critical to swimming. “The fish always swim right off,” says Clayton Spizawka, one of Nimmo’s pool pilots, who likens the process to piercing an ear.

The fin clip is placed on a sheet of Whatman paper, which dries and preserves the sample, and is then placed in a waterproof envelope that guides label with a sample number. Notes including the date, time, location, species, sex, water temperature and other comments, are documented and kept with each sample.

To the average fisherman, hooking a salmon is all about bragging rights and scoring a grip-and-grin photo. But Nimmo Bay attracts a different kind of angler. “The majority of our guests have a deep respect for the fish and a genuine interest in learning about the environment they’re fishing in,” says Spizawka. Guests looking for a more meaningful fishing experience have the opportunity to assist guides as they collect data. “It does take a little bit more time, but most guests are willing to spend a few extra minutes to help with education and conservation,” Spizawka says. “I often say, we’re catching salmon to save salmon because if we don’t do this research now, it’s very possible that we won’t have fish to catch years down the road.”

Guides at Blackfish Lodge, a floating fishing retreat located on a little bay of Baker Island in the Broughton Archipelago, also contribute DNA samples, which are stored at Nimmo Bay Resort and collected every few weeks by Rogers. Samples are then sent to the Molecular Genetics Laboratory at the Pacific Biological Station, a federal fisheries research center, where they are analyzed and added to the current genetic database used to identify salmon from specific river systems. The lab uses genetic markers to build a library of diversity within each river for each species of salmon.

Each tiny fin clip contains large amounts of genetic information that helps researchers understand migration patterns. “Through this program, we’ve been able to gather foundational information from which people can start to ask questions or draw conclusions,” says Rogers. “This information is fundamental when you’re starting to have conversations about how to protect rivers and make decisions about how to best manage salmon and their surroundings.”

Salmon stocks have such specific needs that broad management decisions can have drastically negative effects on the entire ecosystem they inhabit. Should a watershed be opened for logging? Can we fish in a spot without hurting a very specific population of salmon? Having access to the diversity of salmon can help in making these decisions, says Rogers.

To date, the Catch-Clip-Release program has collected more than 3,000 samples, according to Rogers, and is already shedding new light on the area’s salmon population. Samples collected in 2015 and 2016 revealed that the coho that return to the Wakeman River each year are genetically distinct from the rest of the coho in

Fisheries Management Area 12. Research shows they are more closely related to the fish of the Central Coast, rather than those of the northern portion of the South Coast.

Initially, the program only targeted Pacific salmon, mainly coho, Chinook, and chum. Last year, the Ministry of Forests, Lands and Natural Resource Operations approved the Catch-Clip-Release program to collect samples from steelhead, Dolly Varden, rainbow trout, and cutthroat trout. Participation has also grown, with Ocean Outfitters in Tofino coming onboard in 2017. “Our simple little idea has really taken off and empowered the local communities to take control of their future,” says Rogers. “Big problems, like protecting the environment and saving a species, suddenly seems surmountable when we all come together.”

Words: Jen Murphy

Photos: Jeremy Koreski